Modelling

EMPowER

Climate policy is a priority area for the Irish government, underpinned by a robust EU framework. The 2019 Climate Action Plan (CAP) developed by the Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment (DCCAE) details the implementation of climate policies to 2030. The objectives of Climate Action are to ensure that (1) emissions policy targets are delivered and (2) benefits to society are maximised and any harm is minimised.

Decarbonisation of energy systems will be a multi-decadal challenge for government, industry and wider society. Governments use the term “modelling” to refer to a wide range of policy analysis tools that form the evidence base for decisions. Effective Climate Action entails particularly intensive technical and economic modelling. UCD Energy Institute is contracted to provide “electricity systems modelling services” to the Climate Action Modelling Group within DCCAE. This forms part of the national policy modelling capacity that draws on expertise from several different institutions.

Policy Background

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was established to provide a collective framework for greenhouse gas emissions reduction. Climate Change presents a policy dilemma that can only be resolved through international cooperation. For instance, Ireland’s contribution to global warming is inconsequential by itself (our emissions from 1990 are unlikely to contribute more than 0.002oC to mid-century warming) and yet the full impact of climate change will be felt here. International agreement enables countries to capture the climate benefit of their national decarbonization efforts. UNFCCC is therefore critical to the success of climate policy globally.

The UNFCC process originated in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit. Unfortunately, the concentration of long-lived atmospheric greenhouse gases have risen strongly since then. Atmospheric CO2 reached an all-time annual high of 411ppm in 2019 versus 356ppm in 1992. Fossil CO2 emissions reached 37.5GtCO2 in 2018, having rising at an average annual rate of 1.5% over the previous decade. Clearly global climate policy has failed to reverse powerful underlying trends driving emissions higher.

The 2015 Paris Agreement is the culmination of the UNFCCC process. This agreement aims to limit the global temperature rise this century due to human activity to “well below 2oC”. It was formally ratified by the EU in October 2016. Signatories to the agreement submit nationally determined greenhouse gas contributions (NDCs) and agree to review their ambition upwards every five years (the so-called “ratchet mechanism”).

The European Union’s current NDC commits to a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 1990, as agreed in the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework. The latter also set a 2030 renewable energy target of 32% of total final energy consumption. The first revision of the NDC (European Green Deal, 2020) is likely to raise the greenhouse gas reduction target to 50-55%. Also, in December 2019 the European Council adopted a “strategic long-term vision” of carbon-neutrality by 2050 in line with Paris goals. It is fair to say that Europe is at the forefront of climate targets and diplomacy.

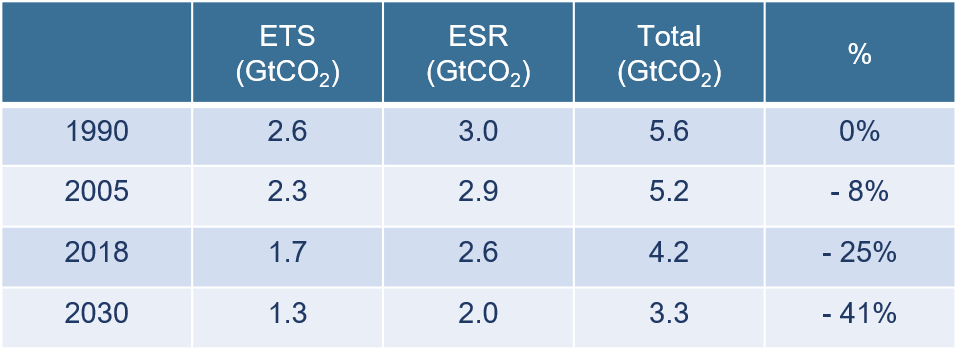

How does EU climate policy translate into climate action by individual EU member states? The Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) has operated since 2005 and is designed to lower emissions in the power sector and large industry by means of an EU-wide cap. ETS accounts for about 40% of total emissions. An emissions target can be set for ETS emissions as a whole, irrespective of the member state in which they arise. On the other hand, targets for most non-ETS emissions (e.g. transport, agriculture) have been assigned to individual member states under “Effort Sharing Regulation” (ESR). ESR and ETS emission reductions targets are currently set relative to 2005 at 30% and 43% respectively. These translate into the Paris Agreement NDC target as shown in the table.

Member states must determine the most cost-effective and equitable pathways to achieve their ESR, efficiency and renewables targets. These are elaborated in National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs), that are part of the Regulation on the governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (2018). Ireland’s binding ESR target has been set at 30%.

Climate Action, Electrification and EMPowER

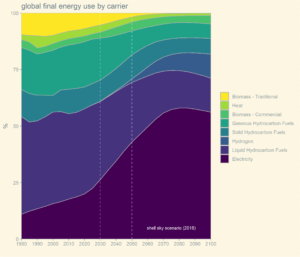

Ambitious climate action entails a very rapid increase in the rate of electrification globally. Figure 2 shows “global final energy use by carrier type” in a scenario in which net zero emissions are achieved by 2050. Electrification, meaning the percentage of global final energy use in the form of electrical energy (rather than hydrocarbons for example), has been increasing at about 2% per decade between 1980 and 2020. This must increase to more than 8% per decade from now until well into the second half of this century to meet Paris goals. Such drastic acceleration in the rate of electrification will not happen spontaneously. It must be facilitated if not driven by strong policy measures.

According to the Climate Action Plan and NECP, electrification contributes to climate goals in three major ways in Ireland by 2030:

- Power generation is significantly decarbonised (falling close to 0.1 tCO2/MWh) even while total demand increases by up to 30% due electrification and digitalisation.

- Transport is electrified through large scale adoption of battery technology.

- Heating is electrified through growth in use of air-source heat pumps and retro-fitting.

Technical challenges of implementing this vision include the variability of renewable power, role of markets and interconnection, unpredictability of consumer behaviour, impacts of new system loads and distributed generation, performance of legacy distribution networks and the interplay of all of these. The probability of a successful energy transition is increased when obstacles to climate action can be identified before they arise.

The EMPowER (Emissions and Fuel Mix, Markets and Costs, Power Flows and Networks, and End Use & Rates of Uptake ) programme at UCD Energy Institute uses a computational modeling approach to these challenges. By simulating the path to future low-carbon energy systems, modelers attempt to discriminate between policy options and scenarios quantitatively.

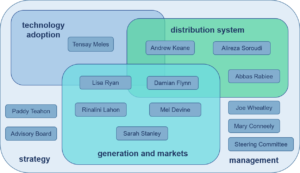

The EMPowER team consists of 5 associated academic staff from UCD Department of Economics, School of Engineering, School of Business, three post-docs, a research student and a policy research expert. Work is divided into three strands (1) technology adoption (2) distribution system and (3) transmission system (generation). Of course, there are very close links and overlaps between each of these strands.

Outputs

Decarbonising Passenger Cars – Gap to target, revenue to the exchequer, and distributional impact

Report for the Department of Transport, July 2002,